Science communication:

Sharing science beyond specialists

Nicole-Reine Lepaute was not only a brilliant calculator: she also played an essential role in spreading scientific knowledge in the 18th century. Her work did not stay within scholarly circles—it helped a wider audience (engineers, navigators, craftsmen, or simply curious minds) understand and use key astronomical principles.

One of her major contributions was her involvement in the Treatise on Clockmaking, written with her husband Jean-André Lepaute. In this work, precise timekeeping and the mechanics of clocks are explained through concepts from astronomy. This bridge between sky science and everyday life is an early form of science communication: making science useful and concrete.

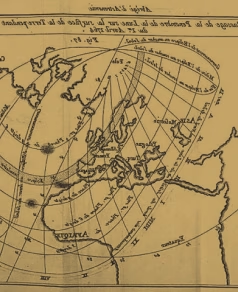

Nicole-Reine also contributed to astronomical ephemerides—true celestial calendars used by sailors and observers. By organizing data about planets and stars, she made celestial movements easier to understand for people outside academic environments.

Finally, by working in a field reserved for men, she helped normalize the presence of women in science. Even without writing a popular book, she inspired other women to follow paths in mathematics and astronomy.

The “Lepaute” asteroid and the flower

The Japanese rose discovered by naturalist Philibert Commerson was named “Hortensia” in honor of the first French woman astronomer. Nicole-Reine Lepaute (1723–1788) was a gifted mathematician: for more than six months, from morning to night, she calculated the return date of Halley’s Comet, at a time when such predictions seemed almost impossible.

In the shadow of her collaborators, Clairaut and Lalande, she contributed to their reputation but was too often forgotten when results were published. This silence is at the heart of the Matilda Effect.

“Making science simple means making it human.”

— Conclusion (Matilda mockup)